Helena Shaskevich, WAJ’s inaugural Interviews Editor, conducts a conversation with Copper Giloth (b. 1952; Fig. 1) about her pioneering work in computer animation and her distinguished contributions to the histories of experimental media art.

Helena Shaskevich (HS): Copper, it’s really wonderful to have an opportunity to chat about your work and career today. I thought it would be best to start at the beginning. You graduated from Boston University in 1976 with a degree in sculpture, and then enrolled at the University of Illinois Chicago in computer programming. This is such a striking transition! I am curious to hear more about your shift from sculpture to programming and what prompted this change.

Copper Giloth (CG): So, somewhere in either 1975 or ’76, I got to meet Louise Nevelson [1899–1988] because her work was being installed at MIT. Since I was being trained as a classical sculptor, building figures, it got me looking back at her early work, and thinking, well, you know, maybe welding might be a route for me that’s more direct and offers more options? So, out of that, in the spring of 1976, I founded a short course on welding at MIT, where I learned several types of welding. I heard General Dynamics in Quincy, Massachusetts, was hiring welders, and so I went and applied for a job, and I got hired!

I graduated [BU] in the spring of 1976, and then I got hired to start in June. I went through a month-long training course, and my teacher was a woman welder from World War Two—I thought this was so cool—like having Rosie the Riveter for a teacher! Our classrooms were these metal buildings, and it was unbelievably hot, just ridiculous. Anyway, I had thought, okay, I can do this: I can learn to weld; I am in the Steelworkers of America union. We were working on these thousand-foot Liquified Natural Gas [LNG] tankers that would hold the liquid natural gas that nobody wants in their ports.

I was working on the hull of the ship, not the aluminum balls that were being made in either North or South Carolina (Fig. 2). In the shipyard, I worked on these sections of the hull that reminded me of Nevelson’s work. I thought, wow, that’s pretty interesting. And then, the important thing that I discovered is that they were using a computer-controlled flame cutter [CNC], which is similar to a plotter except that the plotting pen acts as the flame cutter. That’s how the workers were cutting these big pieces of steel that were then welded together.

I looked at this computer-controlled machine, and I thought, wow, what a great way to cut and design work!

Another important moment occurred when I decided to travel to Africa. My older sister had been in the Peace Corps, and she suggested we go on a trip. And so I quit my job at the shipyards. I’d only been at it for about four and a half or five months. We traveled to Europe and then to Egypt, sailed up the Nile to Sudan, flew over to Chad, and then finally traveled overland through Cameroon and Nigeria. What struck me is just how the people made objects that they actually used in everyday life. I was attracted to the way the ceramics they made were used for daily cooking, as opposed to being placed on the shelf to look beautiful. I just thought, I need to do something else. I’m not going to build figurative sculpture. I don’t know where [I’m going to go] or what I’m going to do, but somehow I need to make objects that are more connected to my everyday life.

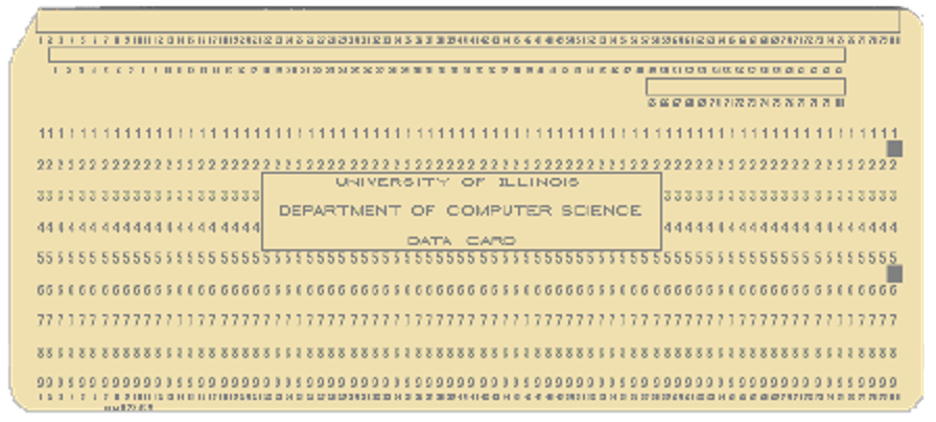

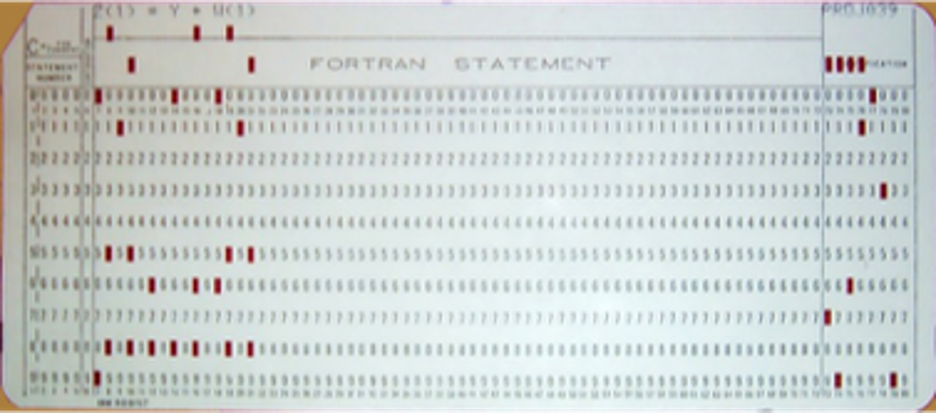

So I went back to the United States and moved to where my parents lived in a suburb of Chicago. I thought, okay, I need to take a course in programming! And so I went to the University of Illinois and signed up for a course in FORTRAN. It turned out, which I didn’t know at the time, that I was taking the last course in FORTRAN programming that was done using punch cards (Figs. 3–4). I just got in at the end of writing this little program, having this machine print it out on cards, and then sticking it into the card reader to run it and wait for the results.e cutter. That’s how the workers were cutting these big pieces of steel that were then welded together.

Having twenty errors in my eight-line program was a humbling experience, but I realized I can work with this process. It turned out that these programming instructions were similar to the methods I used to build sculpture; my approach was very structural with an orientation to systems, and in that way, closely connected to programming. It fit how my mind worked, so it wasn’t hard for me to correct this program quickly. Once I looked at it, once I got down the process of doing it, I went, okay, this is what I did wrong, and it took off from there.

HS: What did you initially find compelling about computer programming? What kinds of projects did you begin working on while a student at the University of Illinois?

CG: I felt powerful being able to tell a machine to do something and then have the machine do it. There was something very liberating in the process. You write this program and you get errors, and then you realize you can correct them, and then it works! It was so satisfying. You just had to learn how to write these commands: this is how you do a loop, or make an array of numbers, or how to use a random number generator. It was very satisfying to get a solution to a problem of one’s own construction. There were a lot of times the program didn’t work—it might not do what you wanted it to do, but then you could change it and make it do something else.

Initially, I was getting assignments while in school: write a series of loops that will draw this equation, or do a series of loops using a random number generator with these kinds of constraints, or make a box, something like that. They were simple programs, but they were a start for me.

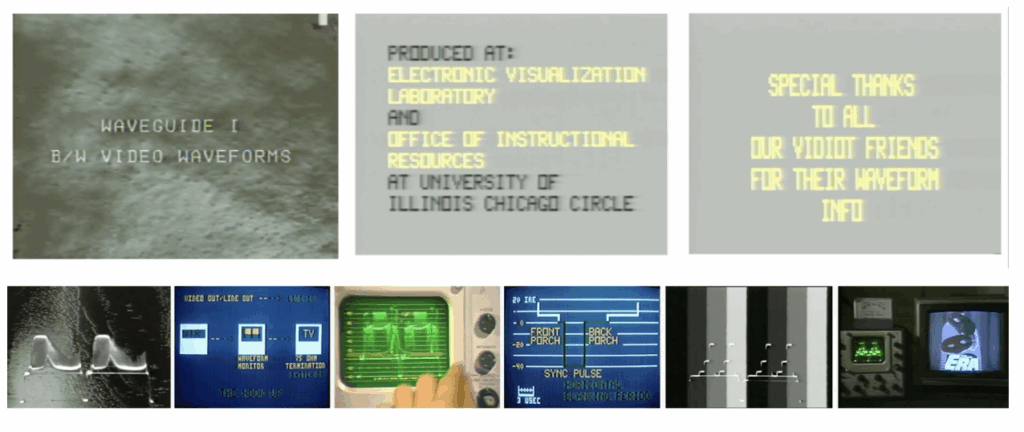

I then began working on educational technology. That’s how I made my tape on how to read and use the waveform monitor (Fig. 5). I was also taking this suitcase computer course on how to program a [Zilog] Z80 [processor] in decimal. So that’s base 16. I had taken assembly language programming on the IBM machine, but now I was learning how to do assembly language on the PDP 11. There was a lot of information that was coming in at this point. I made Waveguide I with Zsuzsa Molnár [b. 1953] as part of a course on instructional technology taught by Raul Zaritsky and Jim Morrissette. To add humor to the piece, we used a bottle of ERA soap detergent to add as a symbol of the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment.

HS: What were some of the first projects you began working on as you shifted away from educational technology? What ideas were you interested in at this time?

CG: While taking these computer science courses, I ended up going to an Electronic Visualization Lab [EVL] event. Dan Sandin and Tom DeFanti were just starting a new joint engineering and art grad program at the time. I was invited to an EVL poster- and screen-printing event, and that’s where I met Jane Veeder [b. 1944], who ultimately became one of my best friends. I applied to the new grad program and got accepted. At the time, I was the chair of the Circle Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU) at the University of Illinois, and I was very involved with the ERA marches. I used the programming language that Tom DeFanti developed, GRASS [GRAphic Symbiosis System], which he wrote for his PhD thesis at Ohio State. It was a vector graphics system and was used by Larry Cuba to make the tunnel graphics in the Star Wars movies. GRASS was a programming language similar to BASIC, but it had a good set of graphics commands.

I learned to program with GRASS, and I made a logo for my CWLU group (Fig. 6). The next project I did was for David Morris, a friend who was a sculptor and worked for [architecture firm] Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. He knew that I was doing programming on this machine. He said, “Why don’t you do a water simulation for me of a sculpture that I’m being commissioned to do in Chicago?” And I said, sure! I figured, okay, I have to build this, I have to build the object. I have to make it look like it’s got flowing water. And then I need to produce a video. It was fun!

HS: Following the water simulation project, you began taking video classes with Dan Sandin, the co-director of the EVL [initially known as the Circle Graphics Habitat], and the inventor of the Sandin Image Processor, an analog computer for real-time video manipulation. Can you elaborate about some of your early video projects?

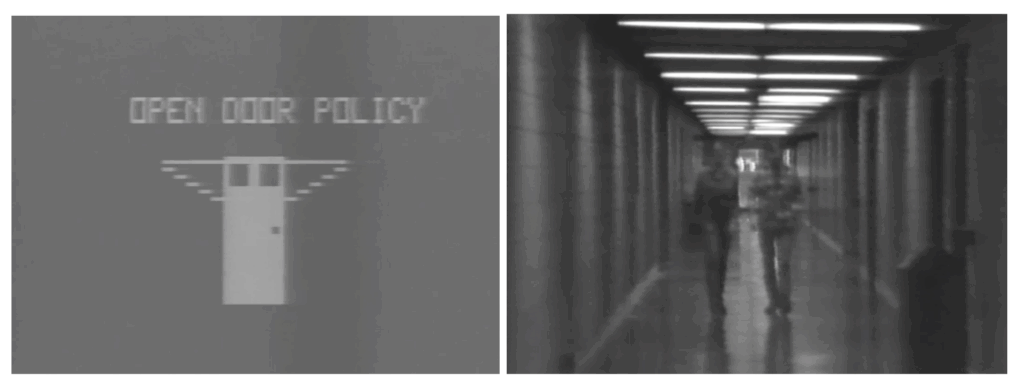

CG: When I started graduate school in the fall of 1978, my first video project was a ridiculous piece about the way men want to open doors for you all the time (Fig. 7; Open Door Policy, 1979). It was all shot on a Portapak [the first commercially available portable video camera]. I thought, oh boy, this takes me right to the work of Nam June Paik. This piece was a response to my annoyance at unneeded door opening.

HS: The work is humorous but also seems to get at some larger issues related to your experiences in art school and coming into your own as an artist. You’ve suggested elsewhere that video and computer programming were liberating for you as an artist.

CG: Oh, absolutely. I think humor is an important part of my work, and a lot of people don’t appreciate it. It was frowned upon in art school; everything had to be so serious. Using humor was a form of release. I was the only grad student in my program at the time who came from a traditional figure sculpture background. It was like the French or Italian Academy—draw, draw, draw, nudes, nudes, nudes, sculpt, sculpt, sculpt, nudes. And I didn’t see the purpose. Other than my printmaking professor and a visiting professor, all my professors were men, and I felt like, okay, I’ve had mostly white men telling me how to make art.

One of the things I liked about programming was that you could talk to this computer by writing an ordered series of commands, and it would send you back errors and sometimes results. But there was no emotion there. It was just like, you screwed up. Okay, <laugh>, fix it, do it again. And there was something about the process being non-judgmental that was both compelling and supportive. The process of working with the computer was self-critiquing. I mean, I did have to show my work to my professors at some point, but still, there was this continual self-critiquing as my programs and my visuals evolved. Programming felt very different from painting, in which you place paint on the canvas and go, oh, I don’t like that and it gets covered or erased, but the process has ended.

It’s true that even when I’m programming in higher-level languages like BASiC, C, or ZGRASS, somebody else wrote these languages. At the time, most of these languages were written by men. So, in a sense, I was just playing with their language. And I did make comments to myself about that at the time. Like, were these men still telling me I did something wrong <laugh> via these automated Error Codes? I decided to ignore that because I thought, at least they’re not being emotional about it. It’s just that something’s wrong in the code. There was still a greater sense of openness and acceptance of difference in the collaborative art/science environment in my art school.

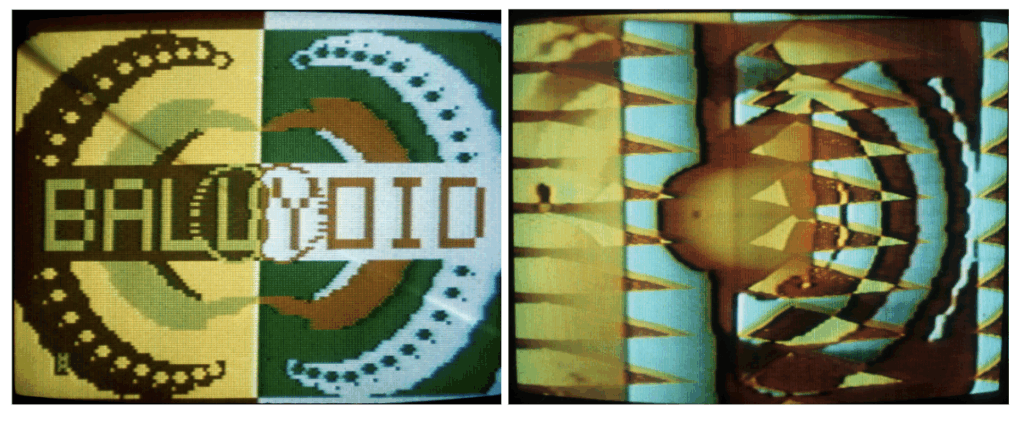

HS: I’d love to discuss some of the technologies you used to make your work. For example, Ballyoid Cardoids (Fig. 8) is in some ways a transitional work. The short video features an animated abstract mathematical equation, whose heart shaped curvatures you programmed with a ZGrass-32 computer and then manipulated with the Sandin Image Processor (IP) to slowly transition across the screen. It is an incredibly lush and beautiful piece, in which the abstract forms touch and mingle as they gently roll from left to right and top to bottom, but it is also the last work in which you utilize a Sandin Image Processor (IP). Can you discuss this piece more, and why you decided to shift away from using the Sandin IP?

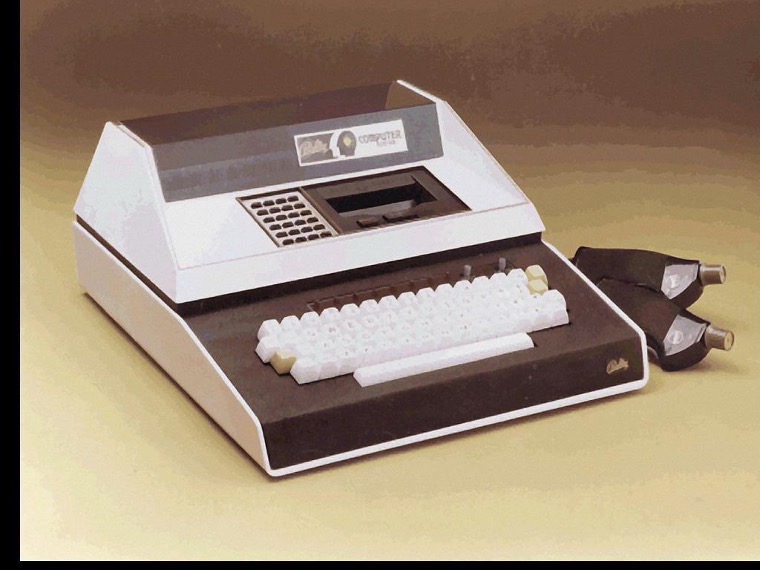

CG: Although I enjoyed learning to use the IP, I mainly collaborated with my fellow grad students to combine it with my GRASS or ZGrass animations. My structured way of thinking was more aligned with these early digital devices, so programming my animations became my primary way of working. Between 1979 and 1980 I made most of my work on a ZGrass-32 computer (Fig. 9). The ZGrass-32 was a Bally Arcade video game combined with additional memory and a real keyboard. Connected to the computer were two handheld joysticks that I used to draw on the screen via simple drawing programs, which I made. I was able to output video from the machine, and my initial works were saved on audio tape. Skippy Peanut Butter Jars (1980), Variance (1979), [and] Feedback, Voice, Trees (1979) were all done on that first [modified] ZGgrass machine.

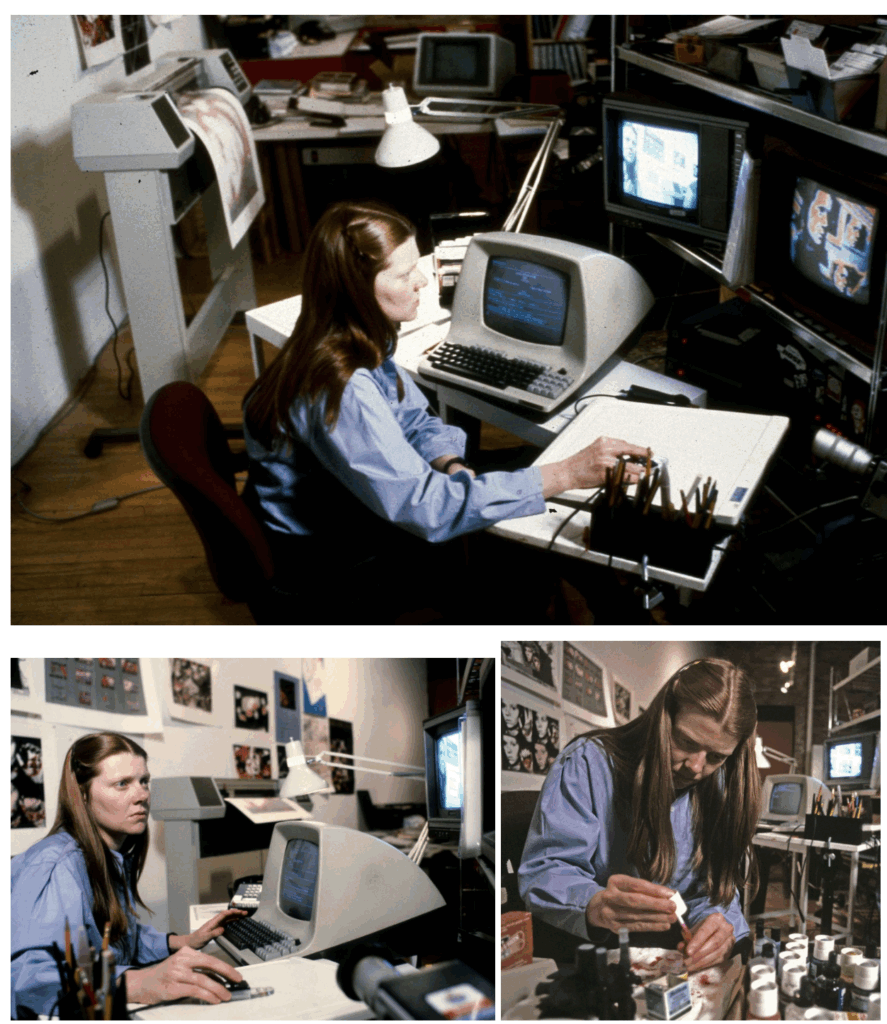

By 1980, I had moved to the new ZGrass system configuration called the Datamax UV-1 (Figs. 10–12). I had a terminal, a tablet for drawing, a computer, and one or two monitors—one video and one RGB, and a disk drive for storage. I also had a plotter to print my work. One of the initial things I produced with the second ZGrass machine was to develop a paint/draw/animation system configured with tools that I had used in my earlier animations. The idea for this system is that it would be made of modules that an artist could easily reconfigure and adapt to their own practice. I used this paint/draw/animation system to make a weather map module, a drawing tools module, and a map-making module. This was also the beginning of how I made my interactive symmetry drawing installations [discussed later, see Figs. 13–15].

HS: Thanks, Copper. I wonder if we might talk a bit about the photos you’ve shared of yourself working in your studio. These photos touch on the complexity, or rather, all the “machinery” involved in early computer graphic art. I think this is difficult for young artists to imagine today.

CG: Yes, I think you’re right. If you think about it, when I’m working now, everything is small. I might have a tablet next to my computer, but everything is in the computer, and I carry it around with me.

HS: How did your work change when you began to transition to the second ZGrass computer, the UV-1? Can you discuss some of the work made with the newer system?

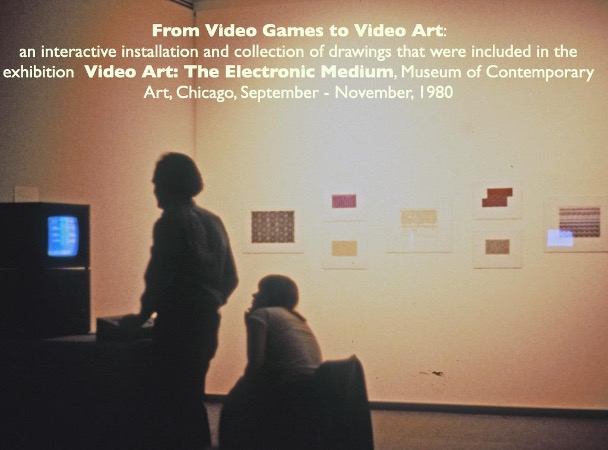

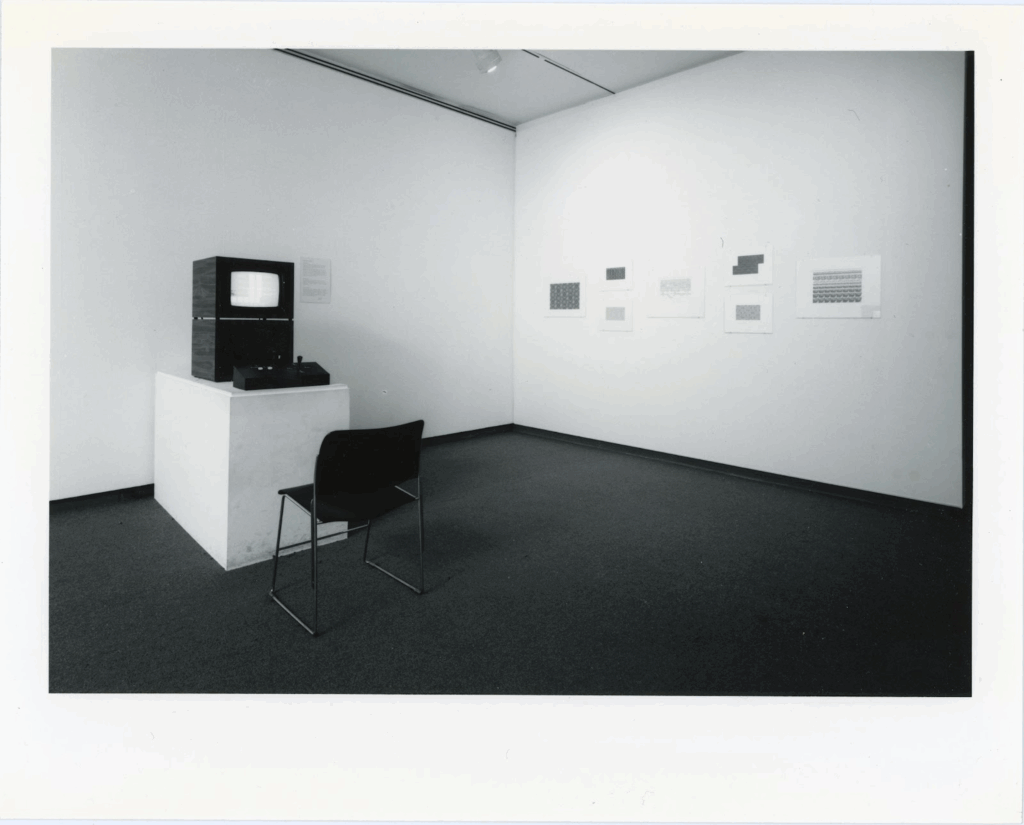

CG: You can see some of the work in the MCA’s Video Art exhibition [Video Art: The Electronic Medium, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, September–November 23, 1980] (Figs. 13–15). It’s an interactive Symmetry drawing program that includes an RGB monitor with a computer underneath and a console with a joystick to operate the system. The person in the photo, a visitor to the show (see Fig. 13), is using a custom joystick to design a small image, which the program enlarges through a grid system. I thought allowing viewers to operate my drawing program was a more direct way for someone to engage with my work.

I’m not sure the Museum of Contemporary Art knew what they were doing at that point. It was just five months after I graduated. And, well, I don’t think they’d ever had an interactive computer installation at the museum!

The man in the photo is operating one of my custom Symmetry Drawing programs, which allowed visitors to make their own version of the computer drawings shown hanging on the back wall in the photo (see Fig. 13). The way the program works is there are several drawing templates available on the computer for an audience-member to choose from. After selecting a template, you choose layout options, and the program makes a whole picture by using some of the seven basic reflections and rotations to create the larger image. And, so, you get to draw your own abstract computer pieces.

HS: Which pieces were shown at the MCA exhibition? Your interactive piece and some of your plotter drawings, correct?

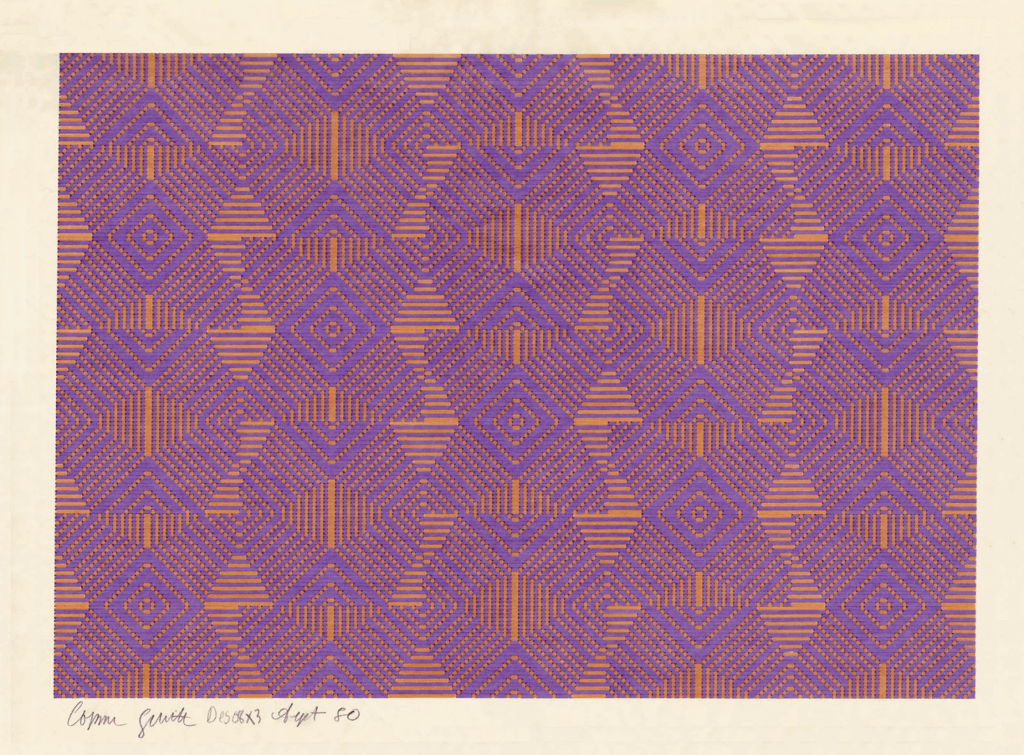

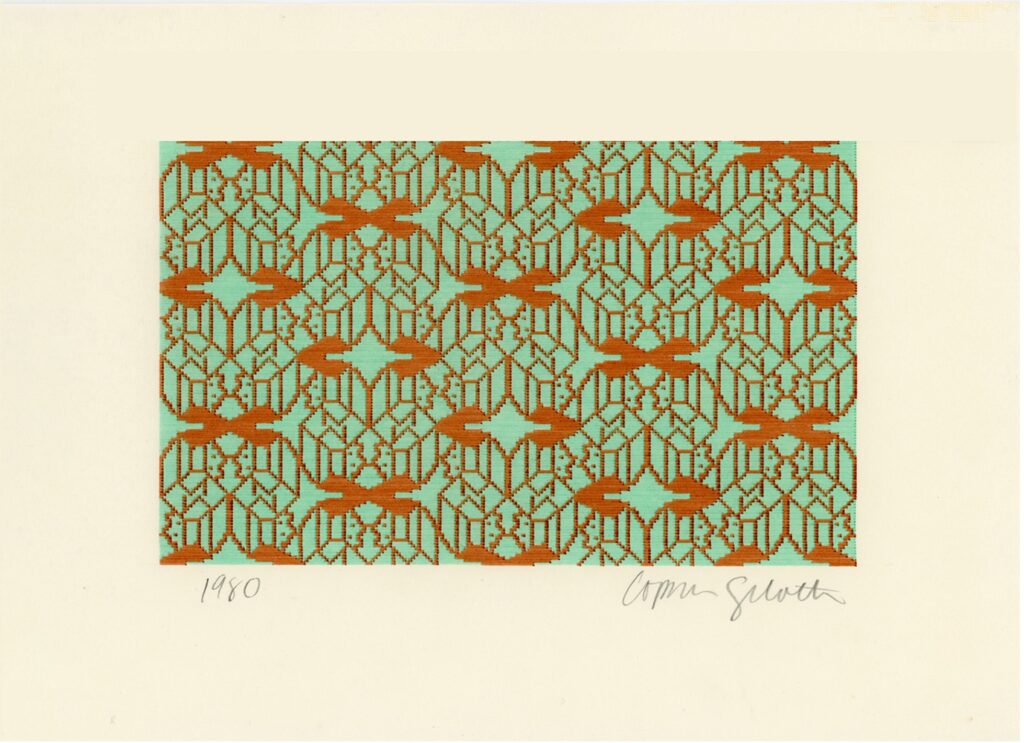

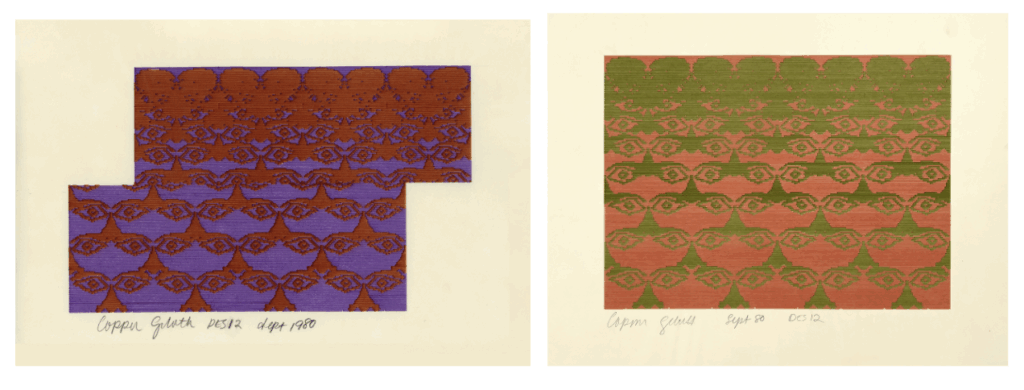

CG: Some of the plotter printouts from the second ZGrass machine were included in the show, like DES 12 [red & purple] (Fig. 18). By making the initial small abstract image and then reflecting it, the image became a pair of eyes. You can see the glitch in DES 12. The plotter had a problem when it was drawing the image and made an incorrect offset on the bottom of the drawing. At the time, I decided this glitch worked, and the museum made a perfect matte for it. DES 12 (Fig. 19) was the same file drawn with different colors, now with the glitch happening during the drawing process.

Right: Fig. 19. Copper Giloth, DES 12 [orange & green], September 1980, 13” x 9 1/2”, HP plotter drawing.

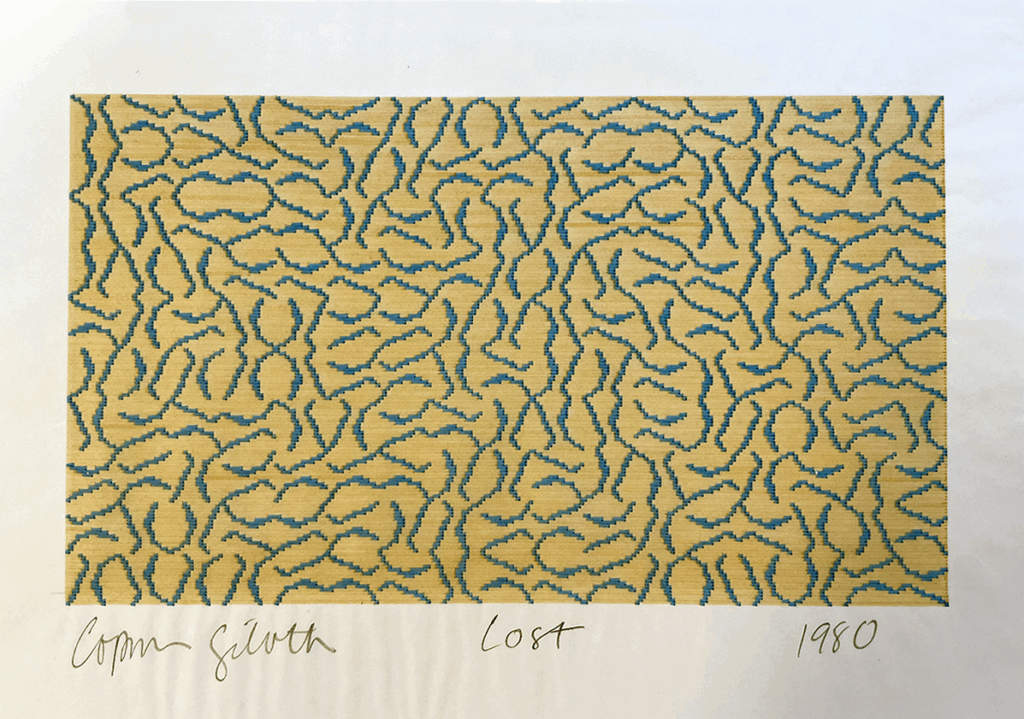

It’s much more difficult to see the glitch in DESLost (Fig. 20) because it’s an abstract element that’s reflected and not rotated. This is my son’s favorite! It’s hanging in his apartment. I spent a lot of time figuring out how I could make something that was based on a basic drawing element, but at the same time appeared random.

Exhibited in “From Video Games to Video Art” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Fall 1980.

I wanted to make a pen plotter work like a video scan on paper. Normally, when you make drawings on a plotter you feed point data to the pen plotter, and it draws lines between each of the points. These are X, Y coordinates on a standard Cartesian coordinate system. But that is not what my program does. The software I used interrogated my raster image and drew a line from left to right. like a video scan. All of my images have only two colors, so the line would be a long segment divided into small sections of two colors. You can see that the printed image has a slight fuzziness to it, like a video screen. I was putting video onto paper.

“I was putting video onto paper.”

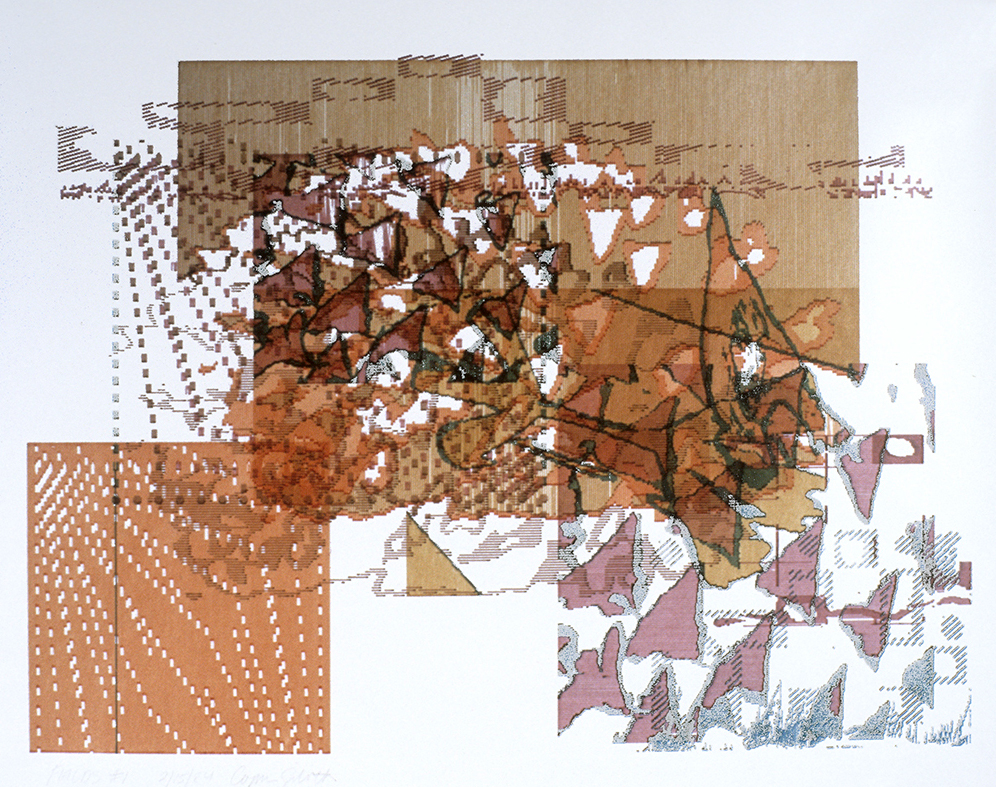

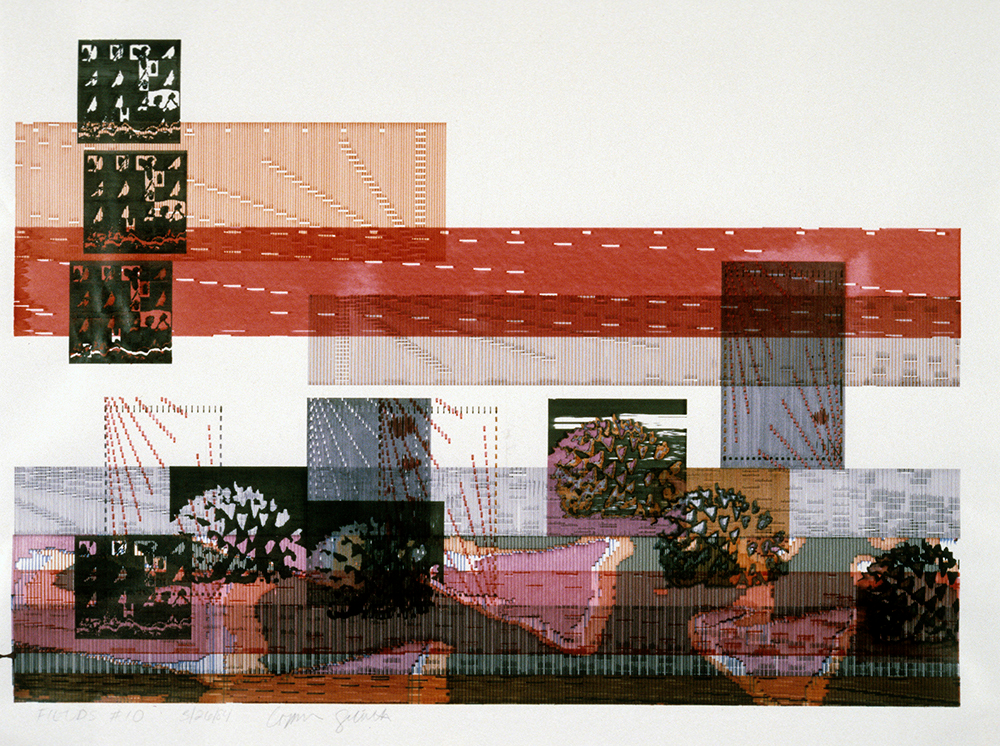

I continued to work with the Zgrass UV-1 system and print with a plotter after the MCA show. This photo, taken sometime between fall 1983 and summer 1984 (Fig. 21), for instance, shows the plotter, and all the images on the wall were from the Field series. The plotter I was using had pens that I could fill with my own custom inks, so I was doing a lot of mixing and trying out different kinds of inks. There were thirty-five drawings in the Field series. Each drawing went through the plotter multiple times, so I ended up working on the series for about six months.

HS: I would love to turn to the topic of feminist politics. Your work raises a lot of interesting questions about what a feminist practice might look like, particularly in early computer graphics. A sense of your emerging feminist political consciousness is evident in a lot of the early work, from the Circle Women’s Liberation Logo to the ERA soap detergent in the waveform video to Open Door Policy. As early as 1979, we see your work developing in two distinct but nevertheless related directions. Pieces such as As I Said (1980) [https://vimeo.com/user39846312], one of my favorites, are explicitly political, while projects like Feedback, Voice, Trees (1980) [https://vimeo.com/user39846312], and Variance 3 (1980) [https://vimeo.com/user39846312] are more engaged with landscape and nature.

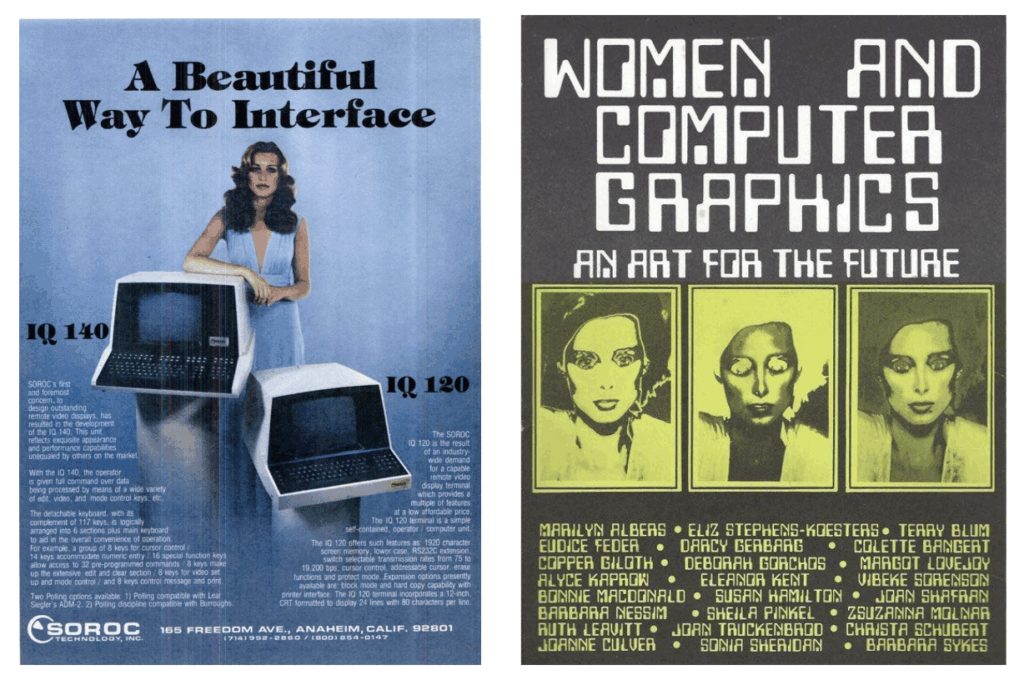

Fig. 23 (right). Poster for exhibition, “Women and Computer Graphics: An Art for the Future,” Olin Hall Gallery, Roanoke College, Salem, VA, November 5–January 25, 1983 (or 1984).

CG: I was often questioned when I was speaking about my work during the 1980s, about how a feminist artist could simultaneously make work like As I Said, and my abstract/landscape plotter drawings.

I thought, they do belong together. I was stunned that people would ask this question. I had other things to say. You can see in Feedback, Voice, Trees, but also in Skippy Peanut Butter Jars and Variance, that I’m responding to the world around me. I’m looking at the landscape, which is something I’m really interested in because I move in the landscape. The hostility towards that surprised me. People thought I was diluting my message by making landscapes because they weren’t explicitly political. Just the fact that as a woman I was out doing this didn’t seem to be enough. Creative computing could be a really hostile space. This ad from 1978 (Fig. 22), for instance, is what I would see every day, and this is how women were seen in the early 1980s. Ads like this were everywhere!

“Creative computing could be a really hostile space.”

HS: Works like Skippy Peanut Butter Jars, another favorite <laughs>, showcase the ways in which you bring a sense of humor to feminist projects. Skippy Peanut Jars, which aired on PBS in 1980 and was later presented at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1982, tells the story of your decision to become an artist as a young girl. You talk about looking through your father’s art books and seeing all these depictions of nude female figures and then practicing drawing these figures and, finally, hiding these drawings in empty peanut butter jars. Viewers listen to this story as they see digital drawings of a nude female figure pop up and multiply across the screen.

CG: I think at that point I was reflecting on my whole life, how I had grown up, and the home we had moved to near Homedale, New Jersey, where my father worked at Bell Labs. I was a Girl Scout at the time, and I had this small campsite in the woods behind our house. I was very interested in art and actually made one of my first figurative sculptures during this period (Fig. 24). My father had brought home some discarded copper wire. And so I started making these wire sculptures as I was trying to envision myself as an artist. And then I looked in one of my father’s college art books, and I saw all these nudes!

These works were made by Giloth as a child from the discarded spools of copper wire acquired by her father from Western Electric.

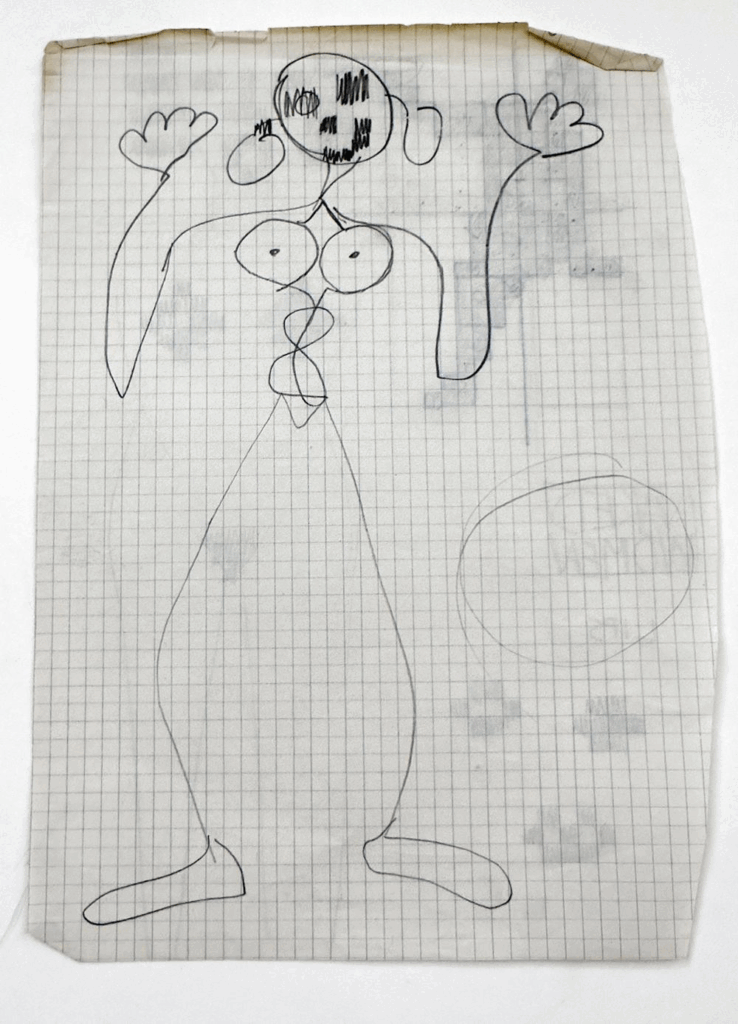

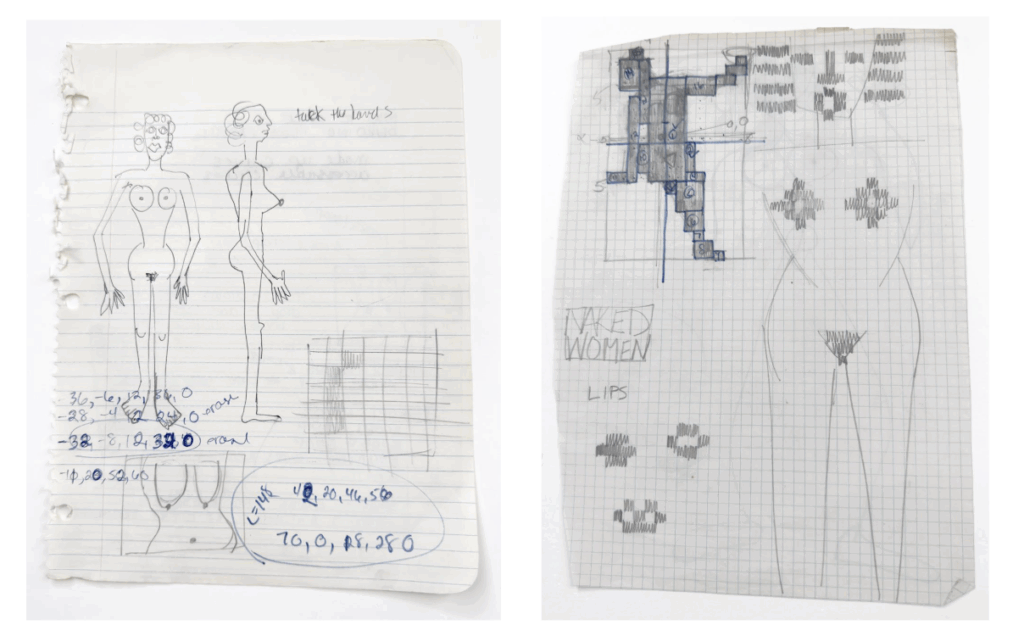

During the fall of 1979, a graduate faculty member in the Computer Science / Engineering department at UIC gave me a small Bally/ZGrass computer to use at home. I was living in an apartment in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, aand had turned a tiny room in that apartment into my studio. Working with the Bally computer, I decided to unpack my life experiences through programming. I had learned and practiced the fundamentals and felt ready to go in my own direction. I’ve said this before, but it felt like I was never allowed to be funny in art school. I think, under different circumstances, I could have been a comic book artist. So, I began thinking about my experiences as an artist, and then I remembered burying these images of nudes in peanut butter jars in my backyard as a child. And I happened to use Skippy peanut butter jars because we had a lot of them and often reused them to store odds and ends like nails, screws, and washers.

I think the fact that I got the opportunity to take a computer out of the lab into my little tiny studio on 18th Street in Pilsen is what allowed me to make the work. I had all my art history books there. And you can see from my drawings (Figs. 25– 26) that I’m referencing all of these famous paintings of the female nude.

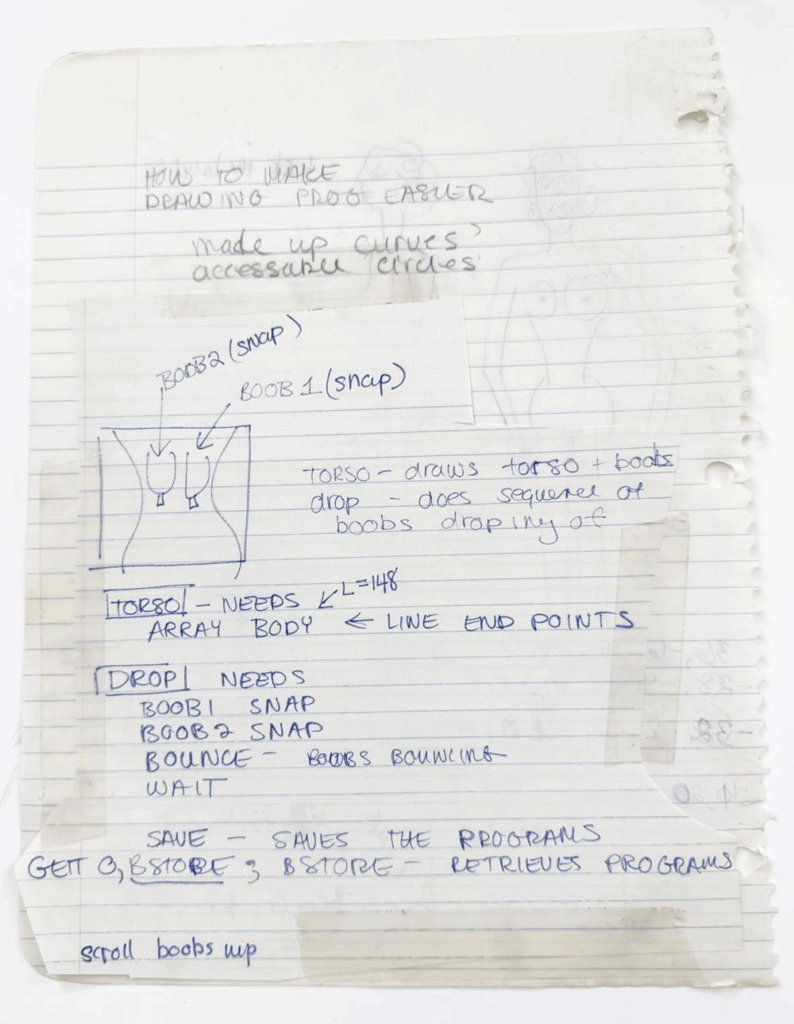

This drawing (see Fig. 26), for instance, is a reference to Alexander Calder’s wire drawings. I was exploring how to make the pixels work (Figs. 27–28), and then I sketched how to make the boobs drop (Fig. 29). At the time, I was also involved with the Circle Women’s Liberation Union at the University of Illinois, which was my first experience overtly speaking out about women’s rights. I was very conscious of how women were represented in art and popular culture. Pixelating famous paintings of the nude female figure—by male artists, from Botticelli to Manet, allowed me to encase my displeasure in humor.

HS: So, you graduated from UIC, and in 1985 accepted a new role as an Assistant Professor of Computer Animation and Drawing at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. This has always seemed to me like such an interesting moment in your artistic trajectory. Narrative Information, a small, but significant solo exhibition of your work at the time, opened shortly after you started at UMASS in February of 1987. The works in the show seem to almost suggest a return to sculpture.

CG: Yes, it was during the process of making the pieces in that exhibition that I started thinking about sculpture again. I had actually started working on Clothes Hangers (1985–87) before arriving at UMASS.The issue of abortion rights was in the news at the time because the government wanted to take away support for abortions for people on Medicaid. I made the video animation for Clothes Hangers in the spring of 1985 with the software VideoWorks [made by the company Macromedia; Videoworks evolved into the software product Director] on an early Mac computer. That piece was shown in San Francisco at the 1985 SIGGRAPH conference, but it was displayed in a way in which it almost disappeared behind other works, including one with a pixelated Olivia Newton-John singing one of her songs <laughs>.

Initially, there wasn’t a program for me at UMASS. I was in a traditional art department, teaching several sections of 2D design, and only one computer art course. I had to order and set up all of the equipment, including computers. In 1987, we finally got twelve Amiga computers. When that happened, I immediately rewrote the animation for Clothes Hangers to work on it, which is about abortion, and when I made it, I crafted the language, as a story, to more directly include data about the interventions by the government.

One of the challenges with the abortion issue was how to incorporate, visually, the existence of the religious right [political movement]. I started experimenting by creating a column and placed the computer monitor on top of it. By projecting a photo of the US Supreme Court over that column-computer set-up, I was able to have the work cast a shadow of a cross over the steps of the courthouse.

It was comforting and natural for me to be working in a sculptural way without having to make a classical figure. By integrating computer animations with sculptural objects, I thought that I had finally found a way to work with the body without it being physically present. For me, sculpture was a reality. It had a physicality that resonated with me in a similar way to how the structure of a computer program serves as a means of weaving a story together. When combined with my computer work, the sculptures evolved into installations that could convey my emotions through objects.

“By integrating computer animations with sculptural objects, I thought that I had finally found a way to work with the body without it being physically present.”

HS: You’ve recently received a lot of attention for one of your later animations, Modeling the Female Body (1994), shown at the Digital Witness exhibition at LACMA. The piece tackles a prevailing theme in your work and reminds me of your references to paintings of classical nudes in Skippy Peanut Butter Jars (see Figs. 27–29).

CG: Thinking back to 1994, it marked a low point for me. I was going through my separation from my husband while reviewing disturbing images of computer-generated women in my professional society, images primarily created by male researchers, which was quite depressing. I felt unhappy in the Art department and was preparing to transition to part-time Academic Computing, where I would be able to make significant decisions about how to help faculty incorporate new technologies into their teaching.

I was trying to figure out how to create art while also being an administrator, a mother, and navigating a field that often accepts the creation of abusive images of women. Sigh.

Modeling the Female Body was showcased at SIGGRAPH ’94 in Orlando, Florida, during the Electronic Theater, their most prestigious event. They put me through a lot to obtain permissions for all the short segments displaying my work. SIGGRAPH, the organization, was concerned about presenting it, even though I was operating under fair use. Pixar was the only company that wouldn’t allow me to use the “big-boobs” mermaid! Many people were annoyed to see my compilation, but others understood my perspective. Eventually, everyone forgot about it. I don’t know, maybe four or five years ago, people began to realize that I had worked on this much earlier and they were surprised that I had ever tackled the topic.

But I was so angry at the time. I want to add a side note to this. That same year, an event called the College Bowl took place at SIGGRAPH, a conference held every few years, where teams from universities compete. They also do this with high schools, but we participated in a computer graphics College Bowl. There were teams from Princeton, MIT, Caltech, Stanford, University of Toronto, University of Illinois, Chicago, and a few other schools. My team was the only one with two women and one man. I was the art expert, Sally was the entertainment expert, and John Hart was the computer scientist on the team. He joked that he would wear a skirt if the rest of us did, so we became the team of skirts. It was amusing. There was a lot of humor surrounding the whole event. We were quite performative in our skirts, and our team ended up winning, which was shocking given our competition, but we were an interdisciplinary team. The questions covered art, entertainment, and computer science research, and we had three team members with different disciplines. That year, I both made everybody hate me for my piece, “Modeling the Female Body,” but then they were shocked at how much I knew about my academic field.

It was both a hilarious year and a very difficult one. I wondered if I would critique anything about SIGGRAPH in the future. I thought, okay, I’ve made my statement. When I attended the Electronic Theater this past year, there were at least two pieces about getting your period. There have been many changes, and a lot of remarkable work by women and artists included in the evening program. There is progress, yet there are areas where nothing has changed.

HS: So, I think there is a lot more we can talk about, but I wanted to ask one last question for now. Do you have any plans for your archive or how it might be managed and preserved in the future?

CG: I don’t know that I’ve thought about my archive; I’m barely holding it together here! <laughs> It was great that I kept all my stuff because it was very nice to see my drawings for Skippy Peanut Butter Jars in the recent exhibition you curated at Microscope Gallery in June 2025 [June 5–July 12, 2025]. But, of course, I discovered them when I was talking to you, so that’s why they’re there!

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Notes:

Copper Giloth’s papers and presentations can be found at:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Copper-Giloth

Additional documentation of Giloth’s artwork can be found on her Vimeo site: https://vimeo.com/user39846312

Examples of Giloth’s Wisconsin series of plotter prints:

Examples of Giloth’s Field series of plotter prints: