Women Artists and Artisans in Venice and the Veneto, 1400–1750: Uncovering the Female Presence

Edited by Tracy E. Cooper, in conjunction with Melissa Conn

Amsterdam University Press, 2024

Assembled and introduced by Tracy Cooper of the Tyler School of Art and Architecture in collaboration with Melissa Conn, Director of Save Venice Inc., this collected volume marks a pioneering contribution to our understanding of early modern Venetian women visual artists, most of them painters but some working in embroidery, stone carving, or other media. The eleven essays in Women Artists and Artisans in Venice and the Veneto, 1400–1750 belong to a centuries-long effort—one that dates back to early modern defenses of women by women, as in the writings of Venetian author Moderata Fonte (1555–1592), and one that entered modern history through the works of trailblazing women like art critic Julia Cartwright (1851–1924) before gaining momentum in the 1970s and 1980s—to bring women out of the shadows of history and to bridge the fault lines of historiography. The present volume builds on a growing body of scholarship and recent groundbreaking exhibitions focused on reconstructing—and reconnecting with—the lives and work of female artists in Bologna, Rome, Florence, Naples, and other major cultural centers in the early modern era by elucidating women’s artistic production, techniques, and working processes across artistic media as well as their private and public lives, professional networks, and communities.1

Unlocking the richness of this history poses many challenges. As editor Cooper notes in her introduction to the volume, multiple obstacles impede our understanding of early modern female artists, as women’s artistic output was overlooked in favor of work by their male family members and workshops; was bypassed by the Academic patriarchy; and was glossed over by the predominantly male authors of their biographies—in the unusual cases when those biographies were written at all. Women Artists and Artisans in Venice and the Veneto, 1400–1750 not only offers a series of informative case studies (some more familiar than others) that bring female lives to the fore but also illuminates innovative approaches to the critical reading of documents and biographies, to the close visual and comparative analysis of works of art, and to the examination of new evidence made visible by modern conservation treatments.

In chapter one, Babette Bohn, who specializes in early modern female artists in Bologna, addresses the problems of reconstructing the lives of early modern female artists, summarizing what we now know—and the many uncertainties that remain—about women who practiced their art in Bologna, Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples. Bohn, whose groundbreaking work on Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614) has elucidated the favorable conditions for women artists in Bologna, points out that biographical and documentary sources offer only an oblique perspective on the lives and working methods of early modern women. Misconceptions have thus arisen about how women artists were trained: The widespread assumption has been that most training occurred under male family members (for instance, Chiara Varotari, 1584/5–after 1663) or in the convent, but numerous women, Bohn shows, were trained by male artists outside of their families (such as Diana de’ Rosa, 1602–1643), and others by female artists and artisans, including Camilla Lauteri (1649/59–1681), who may have been mentored by Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665). The challenges of attributing their works, moreover, many of which were credited to male members of the workshop, remains an ongoing issue. Bohn concludes by highlighting data that document female artists working in seventeenth-century Bologna, where the number of women far exceeded that of their peers in Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples, and where the greatest number of female artists were trained in workshops that were not associated with their families. Although more questions than answers still surround the study of early modern women artists, Bohn encourages scholars to pursue inventive pathways in their efforts to reconstruct these women’s histories.

One technique employed in the volume’s essays is to closely examine the nuances of language within documents and biographies, seeking to overcome the difficulties of reading between the lines. Another is to analyze images with a similar level of scrutiny. Employing both methods, Louise Bourdua’s contribution takes up the challenges of identifying late medieval and early modern Italian taiapiere (also called tagliapietre), female stone carvers and/or stonemasons, whose names have remained unknown, unlike Properzia de’ Rossi (c. 1490/91–c. 1530), the Bolognese sculptor of stone and peach pits whose miniature creations received mention in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Sculptors, Painters, and Architects (both editions, 1550 and 1568). Through a case study of the 1510 last will and testament of a certain Christina taiapiera, daughter and wife of master stonemasons who lived in the parish of Santa Margherita, Bourdua unravels the fleeting presence of female stonemasons and their roles in the workshop both in and beyond Venice, astutely noting that the documenting of these women variously as entaiaresse, sanpietrine, taiapiere/tagliapietre, and lapicidi renders them very difficult to pin down. Nonetheless, Bourdua’s investigation points toward to the presence of women in family workshops in and near Venice, even if there are many mysteries yet to unravel regarding their precise roles. The essay concludes with a compelling discussion of a fresco depicting the Construction of the Tower of Babel (1370s) in the Baptistery of Padua that may picture a female mason in the stone yard. While it is impossible to confirm this identification, the fresco detail is suggestive when considered side-by-side with the documents.

Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman explore the evidence regarding Marietta Tintoretta (c. 1552–c. 1590), daughter of Jacopo Tintoretto and the only active female member of the Tintoretto workshop. La Tintoretta received attention in Raffaello Borghini’s Counter-Reformation iconographic treatise Il riposo (1584) alongside only two other women artists, Fontana and de’ Rossi; she also garnered praise in Fonte’s proto-feminist poetry (1588) and was the only female artist accorded a freestanding biography in Carlo Ridolfi’s book on Venetian painters, Le maraviglie dell’arte (1648). Nonetheless, Echols and Ilchman point out, she is “a name without an oeuvre,” with no firmly attributed works. The authors attempt to address this conundrum by taking another look at the artist through the eyes of the poets and biographers both in and beyond Venice who mention her as well as through new biographical information uncovered in 2004, claimed by its seventeenth-century owner to be the “genealogy of the Tintoretto family.”2 This genealogy is not entirely reliable, however, given that the original document is preserved today only in a summarized translation into Spanish. Problematic, too, are biographies like Ridolfi’s, which underwent their own game of “telephone” as they traveled through different iterations and editions and which abound with fables and metaphorical tropes that blur the boundaries between fact and fiction. Given the challenges of gleaning information from these documents and biographies, Echols and Ilchman propose that we turn to paintings from the workshop, especially canvases attributed to La Tintoretta’s half-brother, Domenico Tintoretto, six to eight years her junior (if her birthdate is accurate—another challenge), with whom she may have painted. It is plausible that some paintings attributed to Domenico may be by his sister’s hand, such as a rosy-hued portrait of the Venetian envoy to Rome (Fig. 1).

Antonis Digalakis reads the vite of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century female artists in Venice within their broader literary contexts. He traces accounts of women artists whose lives, virtues, and physical attributes were fabricated by male authors, notably by biographers Vasari, Ridolfi, and Natale Melchiori as well as by Venetians addressing related topics (e.g., dialogist and guidebook author Marco Bosconi) and by Bolognese treatise writers. Digalakis explores the ways in which literary tropes, metaphors, and tales of mythical women—many drawn from the first-century encyclopedia of Pliny the Elder and from the fourteenth-century De Mulieribus Claris (Famous Women) of Giovanni Boccaccio—shaped stereotypes of female creativity, “female nature,” and female virtues. Whereas male artists garnered acclaim for their virtuosic oeuvre and for their geographic peregrinations, female artists were often portrayed as “worthy women” whose “unusual” talents transcended their gender. In an appendix building on a 2009 compilation of biographies by Julia Dabbs, Digalakis provides a useful catalogue of thirty-three women artists said to have worked in Venice, mostly painters but a few embroiderers, miniaturists, pastelists, and/or printmakers, with a listing of the primary sources that mention them. That several women artists and artisans brought up elsewhere in the volume do not appear in Digalakis’s list, among them C(h)ristina taiapiera, Gasparina Pittoni (second half sixteenth century), Maria recamadora di S.Tomà (late sixteenth century), Andriana Schiavon (first half seventeenth century), and Giovanna Carriera (1675–1737), points toward the rapid expansion in the number of women whose lives and artistic contributions have begun to be recognized but who remain be fully integrated into the art-historical discourse.

The other seven essays offer case studies of selected women artists “at work,” some who practiced their art within the family workshop and others who made their artistic fortunes independently. Maria Adank takes a close look at the women artists and artisans recorded in two account books of patrician husband and wife Marino Grimani and Morosina Morosini: one libro begun around 1570, roughly a decade after the couple’s marriage, and one dating between 1589 and 1604, during which time Grimani was elected doge and Morosini was proclaimed dogaressa. Adank’s essay builds on Monica Chojnacka’s seminal research on early modern working women by using documentary evidence to shed light on the lives, work, business practices, and professional networks of women artisans who produced luxury crafts like embroidery.3 Raising Anna Bellavitis’s argument about the potentially misleading nature of Venetian tax records and other bureaucratic sources, Adank applies Bellavitis’s point to family archives: When women artists worked on private commissions for or with male family members, the patrons’ account books likely often give the men’s names in place of the women’s.4 Adank notes more generally that women from families of modest means, not least those working in artistic families, figure less frequently in Venetian documents than do those of wealthy families; in many cases, the less affluent women must have been entirely left out. Unusually well-represented in the Grimani libri, on the other hand, are numerous female embroiderers (ricamatrici), including an anonymous artisan in a commercial workshop who received forty lire from Grimani and an unspecified but significant number of nuns in multiple convents, one of whom is even named: Maria, recamadora of San Tomà. Adank concludes with a fascinating historiographical note that explores the nineteenth-century proclivity to assign the founding and patronage of several Venetian embroidery ateliers to the influential Dogaressa Morosini.

Diana Gisolfi discusses Chiara Varotari, who was, indirectly, a student of Paolo Veronese and is best known for her skill with dazzling fabrics and meticulously rendered embroidery and lace in the dozen or so extant paintings attributed to her. Daughter to Dario Varotari, who learned the art of fresco from Veronese, and sister to Alessandro Varotari, better known as Il Padovanino, Chiara Varotari is most widely recognized as a portrait painter, but her hand can likely also be identified in a Mary Magdalene and a Susannah and the Elders. Although she survived her more famous brother and continued to paint after his death, and although she received mention in Ridolfi’s biographies of other artists and in Giustiniano Martinioni’s 1663 revised and expanded edition of Francesco Sansovino’s Venetia città nobilissima, et singolare (originally 1581), Varotari was never listed among the members of the Arte dei Pittori in her own time. Beyond her attention to lace and embroidery, Gisolfi argues, Varotari sometimes delved into the inner state of her sitters, as in a signed portrait of the somber Anzola Muneghina, whom Varotari labeled as forty years old and depicted as middle-aged (Fig. 2). Gisolfi concludes with a thesis about Varotari and Il Padovanino that resonates with Echols and Ilchman’s regarding La Tintoretta and her brother Domenico: It is plausible that works attributed to Alessandro may in fact be by the hand of Chiara, who enjoyed commissions independently of her family and who trained younger female artists. Continued research, including close formal analysis and conservation treatments of paintings formerly attributed to Alessandro, may draw more of Chiara’s signature works out of her more famous brother’s shadow.

The next pair of essays takes up two well known, prolific painters who lived and worked in cities outside of Venice, but whose lives and careers converged for a period in the Serenissima: Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c. 1656) and Giovanna Garzoni (c. 1600–1670). Davide Gasparotto reviews the documentary, literary, and visual evidence regarding Gentileschi’s sojourn in Venice from 1627 to possibly 1629. It was during this chapter of her life, Gasparotto argues, that the artist painted the “lyrical and sophisticated … idealized and elegant” Lucretia recently acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum (166; Fig. 3). He proposes that the 1627 publication of four Venetian poems in praise of Gentileschi’s paintings, among them two of her donne forti, a Lucretia and a Susannah, locates Gentileschi’s Getty Lucretia in Venice around the same date. Gasparotto’s discussion of the ways in which Venetian art shaped Gentileschi’s painting is particularly compelling. In the case of a canvas dating from the same years, Esther before Ahasuerus (c. 1628–30; Fig. 4), now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the dazzling surfaces of fabrics bear affinities with the traditions of Tiziano Vecellio and Veronese, while Gentileschi’s placement of the biblical queen supported by two women across from the king, and her original inclusion of an African attendant with a dog (which she later painted out, and which was recently revealed through X-ray investigation), point toward the paintings of this scene from Veronese’s workshop. Following her departure from Venice around 1629/30, Gentileschi’s arrival in Naples in 1630 coincided with that of her younger contemporary Garzoni, an artist widely known for her still-life genre painting whose deep ties with Venice remain less well understood.

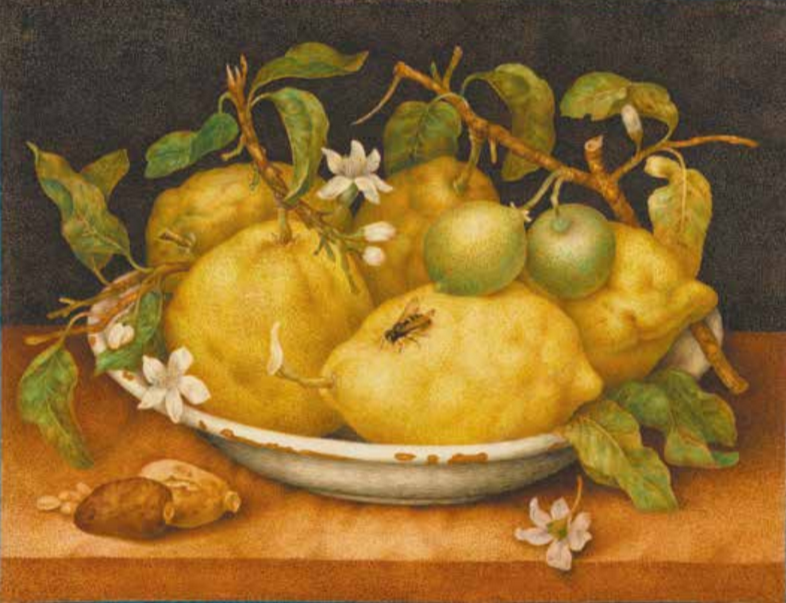

Sheila Barker’s essay makes the case that Garzoni’s vegetal still lifes relate not only to her Venetian roots (her father was a Venice-born perfume maker, her maternal grandfather a Venetian), but also to the culture of magic, animism, and witchcraft in early modern Venice, where the artist spent her teens and twenties. As Barker points out, Garzoni was deeply familiar with Venetian painting through her training with Palma il Giovane, and she produced a large canvas of St. Andrew that was displayed in the Ospedale degli Incurabili among paintings by Palma, Domenico Tintoretto, and other prominent Venetian male artists. It was also in Venice that Garzoni developed her skill at painting miniatures in watercolor, gouache, and tempera on parchment or vellum, as well as her capabilities in calligraphy and music, among the many talents with which Ridolfi credited her (without naming her) in his biography of the painter Tiberio Tinelli, briefly Garzoni’s husband. Using biographical and documentary evidence, Barker suggests that Garzoni’s vivid rendering of fruits and vegetables in such works as Still Life with Bowl of Citrons (Fig. 5) was tantamount to the casting of a magic spell that invoked vegetal matter as protection for the soul. The artist likely had her own soul in mind, Barker ventures, since the artist had suffered trauma in her marriage to Tinelli and in a trial before the Inquisition that had resulted in the marriage’s annulment. These events resonate with similar ones in the life of Artemisia Gentileschi, with whom, the author proposes, Garzoni traveled to Rome in 1630 en route to Naples.

Georgios E. Markou’s essay draws on threads that emerge throughout the volume, weaving together documentary and biographical evidence about the life, work, and artistic networks of “virgin painter” Caterina Tarabotti (1615–1693), an unmarried woman from a wealthy merchant family who never signed her paintings nor, to the best of our knowledge, identified as an artist. Unlike Chiara Varotari, whose biography makes a compelling counterpoint to that of Tarabotti, the latter never had access to a family workshop; she instead received her artistic training in the workshop of Chiara’s brother Alessandro, Il Padovanino. Through her family’s collecting practices, Tarabotti may have met Garzoni, given that a painting by Garzoni’s ill-fated husband Tinelli is recorded in a 1651 family inventory; the same document indicates that Tarabotti had access to works by other women artists, including a sleeping cupid by Gentileschi and a series of sibyls and prophets in chiaroscuro by the otherwise unknown Andriana Schiavon. Tarabotti earned praise as a painter both from Marco Boschini in his 1660 panegyric to Venetian painting and from Martinioni in his 1663 edition of Sansovino’s Venetia città nobilissima. Her only recorded commission, however, an istoria for the ceiling of the church of San Silvestro in Vicenza depicting a miracle by its titular saint, was destroyed by Allied bombing in World War II. As Markou points out, Tarabotti completed this commission alongside—not under—male painters from Il Padovanino’s workshop. Although Tarabotti never took the veil, she acted as an agent for lace-making nuns and their clients, another point of support for the research Adank presents in chapter five indicating that early modern women, both cloistered and lay, exercised significant agency in the business of lace. Markou concludes with the compelling suggestion that a quiet and deeply psychological devotional image of Sant’Agnese now housed in the Accademia may be the only surviving painting by Tarabotti’s hand.

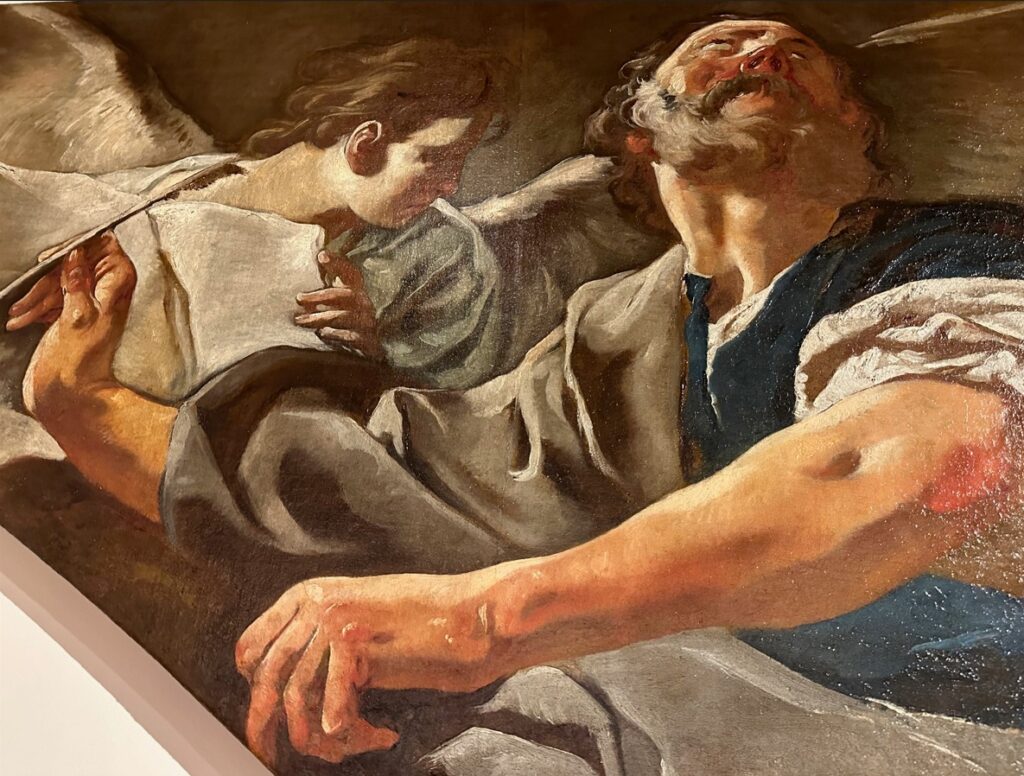

The final pairing of essays juxtaposes the life and work of two eighteenth-century artists: Giulia Lama (1681–1747), “who acquired the greatest honor in her manner of painting,” as Venetian author Luisa Bergalli wrote in 1726 (1703–1779; 213),5 and the most celebrated female painter of Lama’s lifetime, internationally acclaimed portraitist Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757). Both chapters offer a closer look at the artists through the eyes of their peers and through the lens of recent conservation treatments, which have afforded modern audiences a more nuanced look at their creative processes. As Cleo Nisse puts it in her essay, “Lama’s art not only suffers from a lack of historiographical visibility, but also from a literal lack of visibility” (231). A woman of many talents (she was a poet who had studied math and who proposed an invention for a lace-making machine, according to the letters of Abbot Luigi Conti), as well as a close associate of leading Venetian artist Giambattista Piazzetta, Lama painted in a grand, bold manner and sketched vigorous male and female bodies very likely from life. Nisse’s essay focuses on the canvases of the Four Evangelists (c. 1732–34) situated high above an altarpiece by Jacopo Tintoretto as part of a program of twelve spandrel paintings in the Church of San Marziale in Cannaregio. Once barely visible and badly in need of cleaning, Lama’s canvases recently underwent conservation treatment with the support of Save Venice Inc. (Figs. 6, 7), as did Lama’s altarpiece of c. 1736 from the church of Santa Maria Assunta at Malamocco, a likely Virgin Mary kneeling in prayer on a cloud.6 The results were made fully visible for the first time in 2024 in a small—but dazzling—exhibition titled Eye to Eye with Giulia Lama: A Woman Artist in 18th-Century Venice in the sacristy of Venice’s Madonna della Salute, where the paintings could be scrutinized side-by-side with monumental canvases by Titian, Palma, Tintoretto, and Il Padovanino (Fig. 8).7 Lama’s virtuosic brushwork, luminous surfaces, and vigorous figures were quite at home in this pantheon of Venetian painting. While Conti explicitly likened Lama to Carriera, Nisse reminds us that the tendency to compare women to women, rather than women to men, bears a long history.

The volume concludes with Xavier F. Salomon’s essay on Carriera, a celebrated female portraitist who lived and worked in Venice, Paris, Modena, and Vienna; was admitted to the Accademia di San Luca in Venice (as a miniaturist) and to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris; and was praised by a male contemporary for the “extravagant heresy” of painting “the spiritual and unintelligible soul…. Instead of imitating men, you create them” (255).8 By removing some one hundred pastels from their frames and closely examining their backing—bevel-edged wooden strainers stretched with usually blue paper and sometimes with an intervening canvas support, the whole almost certainly prepared before painting—Salomon has yielded some spectacular discoveries, not least a quick pen-and-ink sketch of a bust-length veiled woman presumably by Carriera herself, possibly a self-portrait, on the backing board of a Portrait of a Man now in the Harvard Art Museums. Although Carriera, like so many of her female contemporaries, did not have a workshop, she was assisted by female artists, including her sister Giovanna, who painted alongside her.

Women Artists and Artisans in Venice and the Veneto, 1400–1750 offers much of interest to both students and specialists. Its essays furnish a compelling glimpse at the contributions of early modern female artists to the artistic tradition in and beyond Venice while also pointing toward the considerable work yet to be done. A sumptuous feast of scholarly perspectives and case studies that weave the lives and work of female artists into the multi-textured fabric of the Serenissima, this groundbreaking volume is the first to bring Venetian women artists to the table, placing them in dialogue with one another as well as with the female members of the wider intellectual and creative circles to which they belonged; with the women and men of the collecting elite for whom they worked; with their male artist peers; and with the richness of the arts of Venice.

April Oettinger is a Professor of Visual and Material Culture and the Cushing Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Goucher College in Baltimore, where she is also the Director of the Sweren Wogan Institute for the Study of the Book. She is the author of Animating Nature: Lorenzo Lotto and the Art of Landscape in Venice, 1500–1550 (forthcoming, Penn State University Press) and a coeditor, along with Karen Hope Goodchild and Leopoldine Prosperetti, of Green Worlds in Early Modern Italy: Art and the Verdant Earth (Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

Notes

- Prominent among these recent exhibitions is Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 at the Baltimore Museum of Art, October 1, 2023–January 7, 2024, and at the Art Gallery of Ontario, March 30, 2024–July 1, 2024 (see the forthcoming Woman’s Art Journal review of the Making Her Mark catalogue by Elizaveta Kushnareva). For a comprehensive summary of the many recent exhibitions that have illuminated early modern female artists, see Erika Gaffney, “Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2025,” Art Herstory, December 27, 2023, and “Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2025,” Art Herstory, December 31, 2024. ↩︎

- Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, eds., Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice (Yale University Press, 2018), 63–64. ↩︎

- Monica Chojnacka, Working Women of Early Modern Venice (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). ↩︎

- Anna Bellavitis, Il lavoro delle donne nelle città dell’Europa moderna (Viella, 2016), 24–26. ↩︎

- Luisa Bergalli, Componimenti poetici delle più illustri rimatrici d’ogni secolo (Venice: Mora, 1726). ↩︎

- Nisse identifies the Malamocco painting as an Assumption of the Virgin or as an unidentified female saint in glory (217), but a recent post on the Save Venice website following the conservation treatment of the canvases has put forth an argument that the subject is The Virgin in Prayer: “Giulia Lama’s ‘Virgin in Prayer’ in the Church of Santa Maria Assunta, Malamocco,” Save Venice Inc., n.d. [2024]. ↩︎

- In addition to the recently restored canvases in the Church of San Marziale in Cannaregio and the Church of the Assumption at Malamocco on the Lido, Lama’s public works in Venice include monumental altarpieces for Santa Maria Formosa (her parish church) and San Vidal. ↩︎

- Ferdinando Maria Nicoli, 1703, transcribed in Bernardina Sani, Rosalba Carriera: Lettere, diari, frammenti, vol. 1 (Olschki, 1985): 67–68, letter 23. ↩︎

Image Details and Credits

Figure 1: Marietta Tintoretta?, Giovanni Soranzo (c. 1570), oil on canvas, 42½” x 35”. Private collection. Photo: Sotheby’s.

Figure 2: Chiara Varotari, Anzola Muneghina (c. 1530s), oil on canvas, 25½” x 21”. Museo d’Arte Medievale e Moderno, Padua.

Figure 3: Artemisia Gentileschi, Lucretia (c. 1627), oil on canvas, 36½” x 28½”. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Figure 4: Artemisia Gentileschi, Esther before Ahasuerus (c. 1628–30), oil on canvas, 82” x 107½”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 5: Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Bowl of Citrons (late 1640s), tempera on vellum, 10½” x 14”. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Figures 6–7: Giulia Lama, Mark and the Angel and Ox and St. Luke’s Foot, details from The Four Evangelists (c. 1732–34), oil on canvas, spandrels from the altar of San Marziale, church of San Marziale, Venice, as exhibited in the cloister of the Madonna della Salute, Venice, 2024, each spandrel painting approximately 88” x 93”. Photographs by author.

Figure 8: Giulia Lama, The Virgin in Prayer (formerly interpreted as Assumption of the Virgin or Female Saint in Glory) (c. 1736), oil on canvas, from the church of Santa Maria Assunta at Malamocco, Venice, as exhibited in Eye to Eye with Guilia Lama exhibition organized by Save Venice Inc. in the sacristy of the Madonna della Salute, Venice, 2024. Photograph by author.